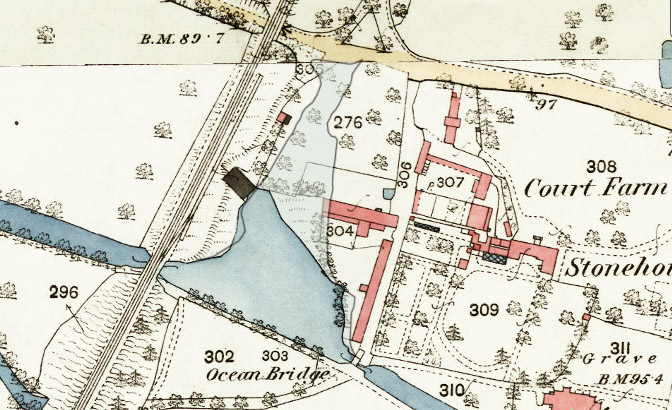

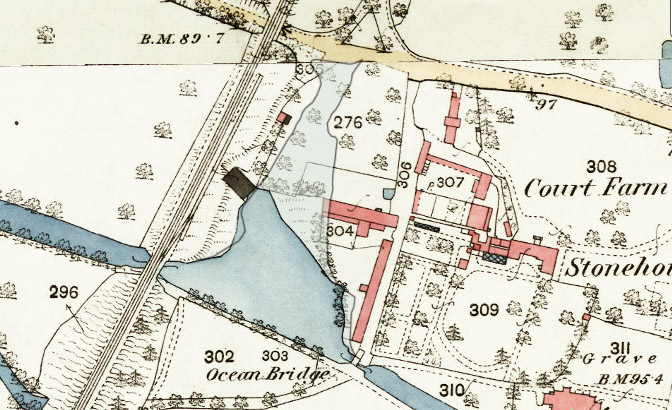

The large area of water known as the Ocean was formed during the construction of the canal when the earthworks for the towpath embankment effectively dammed a stream that previously ran down to join the River Frome below. The wide area of water was not needed much for turning normal trading vessels, but it was used for some cargo transfers and for angling (see below).

The Ocean originally extended up to the main road, and the Stroudwater Company initially believed they owned the whole area. But when they tried to stop a man fishing in 1851, they were unable to produce any proof of ownership. The local land-owner encouraged the north end to silt up, and the matter remained in dispute until a formal boundary was agreed in 1884.

The embankment is one of the major structures along the canal, and it offers towpath walkers fine views over the valley to the south.

By 1836, there was concern about the stability of the top of the embankment, and the water side was supported by building a long stone wall. The specification for the wall called for it to be topped by flagstones linked together by iron dowels, and this became a wharf for delivering coal to Leonard Stanley Mill in the valley below.

The Ocean was put to good use in the early 1840s when stone and other materials were delivered by barges during the construction of the Bristol & Gloucester Railway.

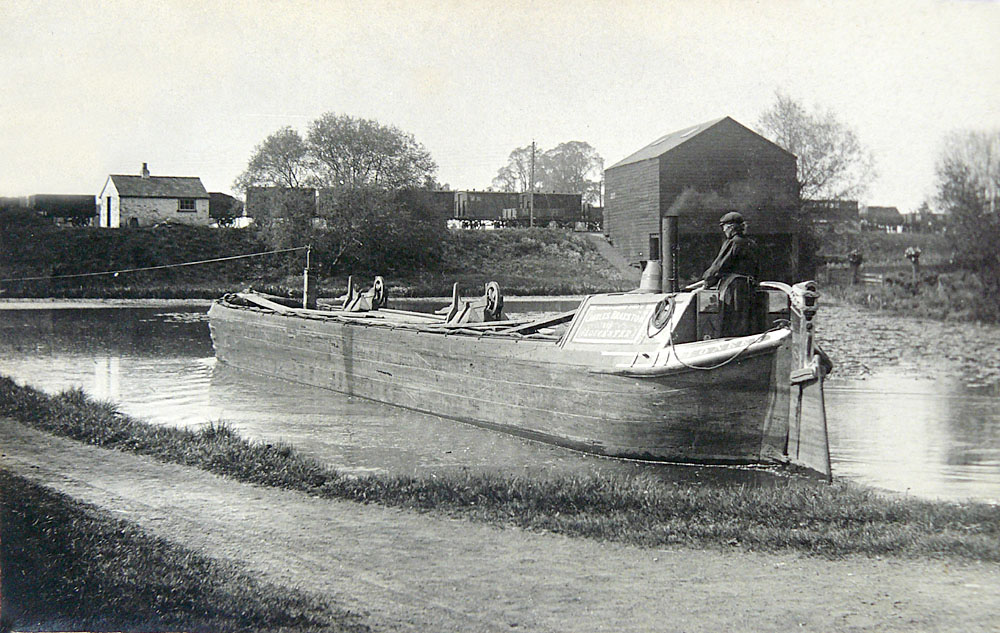

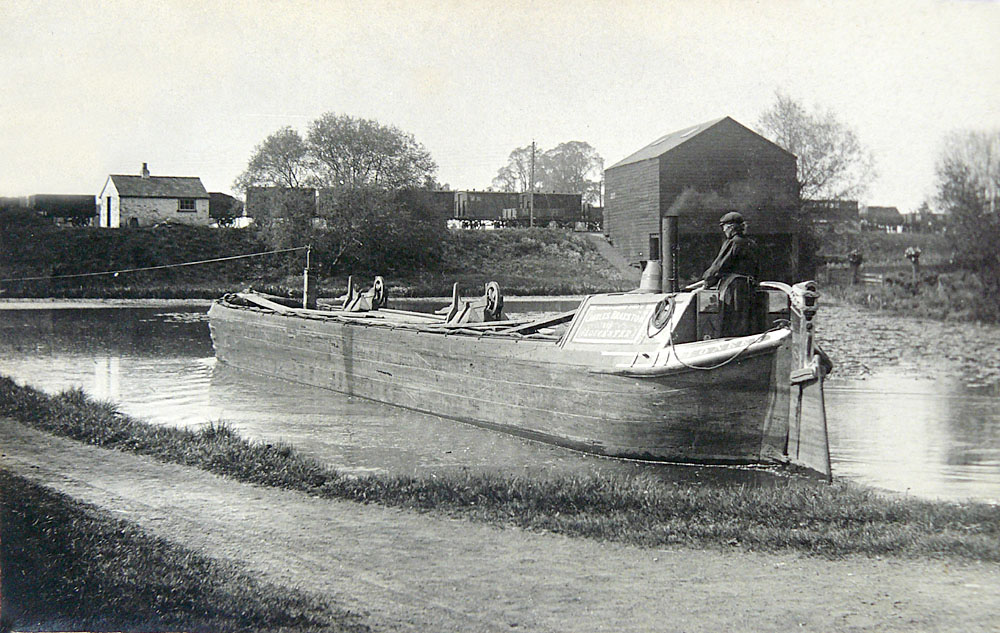

A discharging platform was constructed on the west side of the Ocean, and deliveries peaked during the summer of 1843. In just four months a small fleet of vessels delivered 950 tons of timber from Bristol and 1420 tons of iron rails from Newport. Some of the rails from Newport were sent in vessels that were too big to pass up the Stroudwater Canal, and these were trans-shipped into canal boats at Saul Junction.

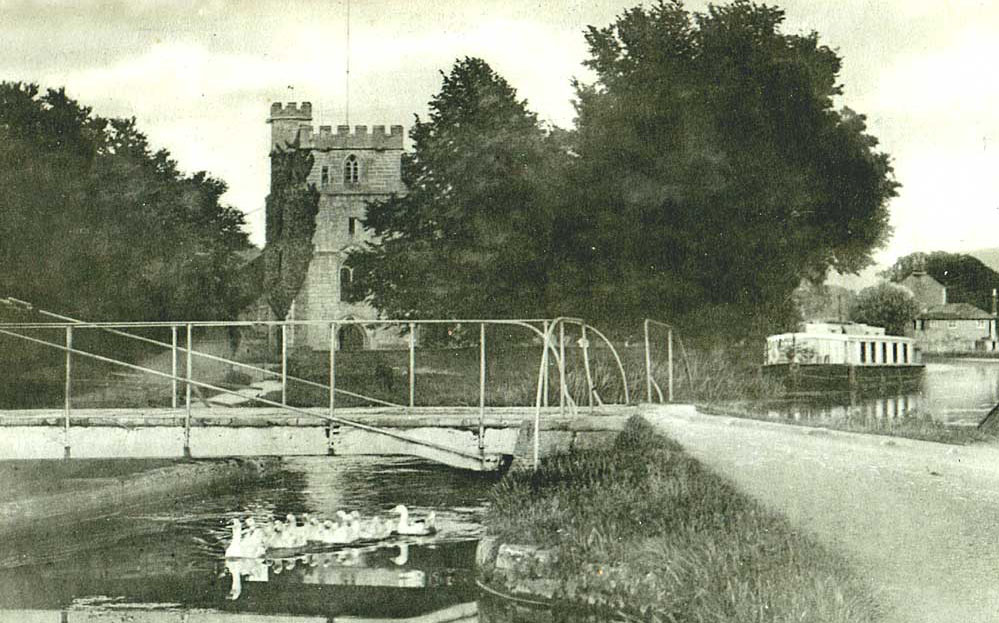

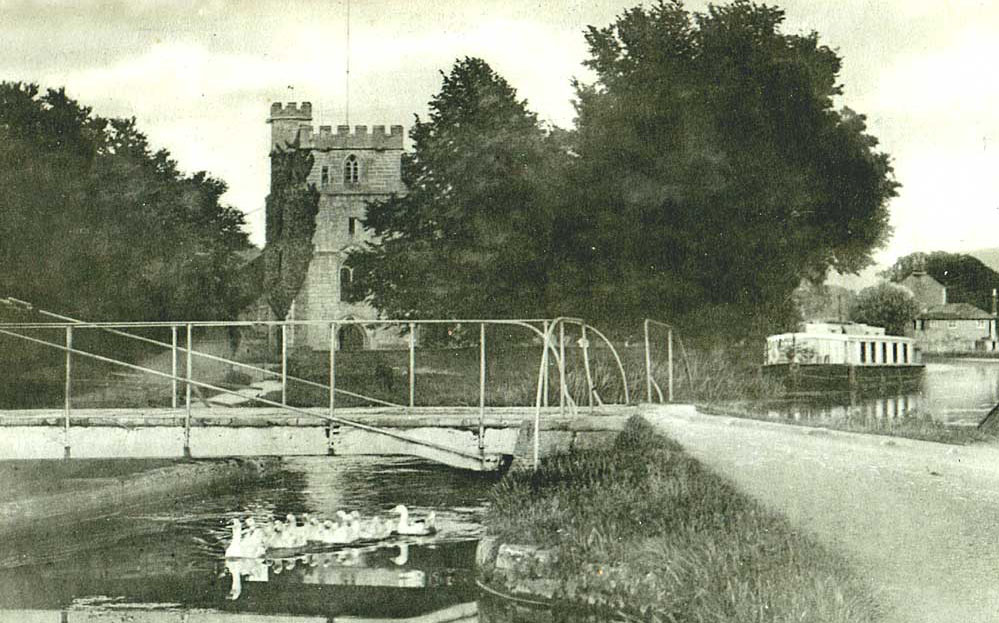

The Ocean was again used by barges after the Bristol & Gloucester Railway Co formed a cut into their embankment with a warehouse structure over – seen in the background of the image. Here goods from the railway could be loaded into barges for delivery along the canal.

For many years, the Stroudwater Company had banned any form of fishing in the canal, but in 1873 they started issuing licences to anglers, and the Ocean became a popular location. A few years later, boys from Wycliffe College started sculling on the canal, and they often used the Ocean as a place to turn their boats, but this caused a problem. In 1890 the Stroudwater Company had to ask the school to stop the boys rowing round the Ocean splashing the water with their oars as anglers were complaining!

The bridge adjoining the Ocean carries a minor road to a hamlet on the other side of the railway embankment that is clustered around the site of the former Leonard Stanley Mill. This mill had a long history of making woollen cloth, the original water power being supplemented by a Boulton & Watt steam engine for which coal was delivered by canal.

Beside the towpath just west of the swing bridge are two large stones from the bridge that was here before the present structure. Each has been inscribed with a poem by Jim Pentney in Haiku style, based on feelings and playing with words. The writing on the stone that housed the swing bridge pivot refers to turning and to the child saint to whom the nearby church is dedicated, and the words on the other stone refer to its location and its origin from the Old Red Sandstone geological series:

Turn tern turn return

Here hear little Cyr cry here.

Ocean ageless wave

Lying still and timeless here

In the Old Red Sand.

For date of formation of the Ocean, compare D1180/10/50 (1776) with D1180/10/2 (1781)

For missing conveyance, see D1180/1/5 p123-125.

For agreed boundary of the Company's property, see D1180/1/6 p400; D1180/10/11; D1180/1/7 p1.

For wall supporting towpath, see D1180/1/4 p109-117

For discharging platform, see D1180/1/5 p138

For deliveries of railway materials, see D1180/4/19 May-Sep 1843

For railway to canal interchange, see D1180/1/5 p138

For start of fishing licences, see D1180/9/4 p206.

For sculling on the canal, see D1180/9/9 p96.